What does not exist in the cultural environment will not develop in the child.

—Dr. Shinnichi Suzuki

DAILY LIFE

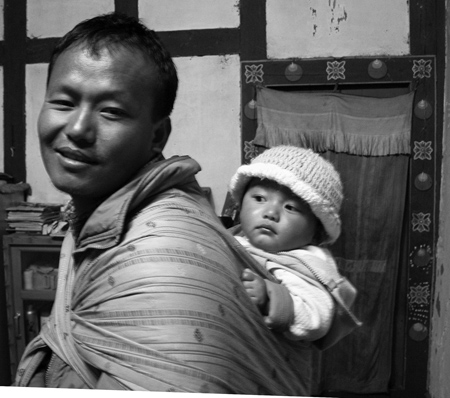

Today the world is becoming a small community, and the attitudes toward those people who have different skin color, language, foods, and songs are more important than ever. These attitudes begin to be formed in the first years of life, as the child absorbs the feelings in the home or infant community.

We can foster a healthy and loving introduction to the cultures of the world by providing, whenever possible, exposure to a variety of music, food, songs, clothing, celebrations, dances, houses, languages, means of transportation, tools—in the home and in the community.

In large cities this is an easy task; just walk around downtown and you will hear the accents and languages, smell the food, even sometimes find the dances and the songs.

But even if we live out in the country it is possible to experience the music through tapes and CD's, and to cook the foods and explore through books. Through such simple and casual introductions children come to understand that all humans have similar needs and experiences. Repetition of exposure and opportunities for conversations on culture can be provided by picture books at this age.

This is the time of the "absorbent mind," the age when a child literally becomes all of the impressions taken in from the environment, it is the time to casually introduce these experiences, not with lessons or lectures, but experientially and sensorially. Use the real names of the food, songs, tools, so the child builds up a vocabulary to match her experiences. Later she will build on these early impressions to make sense of the history and cultures of the world.

A FIRST GLOBE

Why not have the first balls be globes? Large and small soft globe balls are favorites in Montessori communities, not for formal lessons, just for practice rolling and throwing a ball. The shapes of the geographical features will become familiar to the child and make studying geography later like coming back to an old friend.

Near the end of the third year it is a good idea to have a real globe and/or a wall map of the world in the home so reference to places can be made in a tangible, physical way for the child. The child will not understand the scope of space and distance, but will be interested in the colors and shapes and in attaching names to them: "Africa," "Indiana," "The Amazon," etc.

Eventually the real globe or map should be kept in view in the family area, rather than in the child's room, so it will be seen as a real piece of important equipment used by the whole family.

SHARE ON FACEBOOK Share on FaceBook

Newsletters announcing books

#13 Book, Child of the World: Montessori, Global Education for Age 3-12+, March 2013

#14 Book, The Joyful Child: Montessori, Global Wisdom for Birth to Three, July 2013

#15 Book, The Universal Child, October 2013

#21 Book, No Checkmate, Montessori Chess Lessons for Age 3-90+ May 2016

#23 Book, Montessori and Mindfulness, November 2017

#25 Book, The Red Corolla, Montessori Cosmic Education (preparation in the 3-6 class), June 2019

#26 Book, Montessori Homeschooling, One Family's Story , August 2020

#27 Book, Aid to Life, Montessori Beyond the Classroom, March 2021

#28 Book, Please Help Me Do It Myself, Observation and Recordkeeping for the Montessori Primary and Elementary Class, May 2022

Other Newsletters of interest

#2 Montessori Art, Jan 2010

#3 Montessori Cultural Geography, May 2010

#4 Montessori Parenting/Teaching, Aug 2010

#5 Montessori Home Environment, Nov 2010

#6 Montessori in Sikkim, Jan 2011

#7 Montessori Math, Apr 2011

#8 All 2009-2011 Newsletters, May 2011

#9 Montessori Grace and Courtesy, Aug 2011

#10 Montessori Biology, May 2012

#11 Practical Life, Real Life, Aug 2012

#12 Happy Children for the Holidays, Dec 2012

#16 Montessori Language, Apr 2014

#17 Swaddling, Caring for Others, Authentic Montessori. Nov 2014

#18 Concentration, Where the Magic Happens!, May 2015

#19 Michael Olaf Montessori Company, Nov 2015

#20 Cosmic Education, Feb 2016

#22 The Music Environment July 2016

These books speak to anyone wanting to understand Montessori. They are based on the author's fifty years of experience as a Montessori teacher and administrator, speaker, school consultant, and examiner for Montessori teacher training courses. Some have been translated in other languages, the English versions are available from Montessori book suppliers and online.

QUOTING BOOKS

Permission is granted to quote up to 500 words at any one time—on websites or school newsletters or social media—from any of these books, as long as a link back to the book is provided.

AUTHOR'S WEBSITE, Montessori work over the years, art and international blog, SUSAN

MICHAEL OLAF Montessori information MICHAEL OLAF

MICHAEL OLAF Montessori shop BOOKS & MATERIAL

This page was updated on May 10, 2022

|

Madame Montessori,

Even as you, out of love for children, are endeavoring to teach children, through your numerous institutions, the best that can be brought out of them, even so, I hope that it will be possible not only for the children of the wealthy and the well-to-do, but for the children of paupers to receive training of this nature. You have very truly remarked that if we are to reach real peace in this world, and if we are to carry on a real war against war, we shall have to begin with children, and if they will grow up in their natural innocence, we won't have to struggle, we won't have to pass fruitless idle resolutions, but we shall go from love to love and peace to peace, until at last all the corners of the world are covered with that peace and love for which, consciously or unconsciously, the whole world is hungering.

— M. K. Gandhi, 1943

Today our world is shrinking and we have finally learned to cherish diversity—economic, racial, all kinds—to prepare children for living in the real world. Gandhi's desire is coming to pass.

There is also an increasing awareness of the importance of teaching students the value of helping others. This is an important element in the child's world view, and in developing a concern for people all over the world, and people of all parts of society.

TEACHING GEOGRAPHY

We are very fortunate in the United States to be living in a melting pot of cultures. Even the Native Americans came from somewhere else. This wonderful living lesson in geography teaches us that the main difference between us is when we came to our country and why.

The study of geography and of history revolves around the needs of all humans for such basic things as food, housing, a means of transportation, clothing, and the mental and spiritual needs for work, play, and worship. In the early years children are given concrete examples, stories and pictures of people all over the world, in order to build a foundation in geography and history.

The first lessons center around how people have developed a culture because of the place where they live. How and why are the people living north of the Arctic Circle different from those living near the equator? This attitude provides a healthy, non-judgmental, non-ethnocentric, non-nationalistic, basis of exploration of peoples of the world.

The seeds of the study of history are given through experiences of ethnic foods and music, objects, pictures, and books. Later children will build on the impressions taken in during this time of the absorbent mind, the age when they literally become all of the impressions taken in from the environment, to make sense of the history of the world.

GLOBES, MAPS, AND FLAGS

The more easily available a globe and map is to a child, the more often it will be referred to and the more geography will be learned in a very simple and enjoyable way. In providing experiences for the child we move from the general view to the specific—from the whole earth to continents to countries to counties, then towns and neighborhoods.

I remember one day my oldest daughter, then age three and recently having begun attending a Montessori school, was watching me, along with some of her older friends (ages six and eight), pour some beaten eggs into a skillet. She said "That looks like Africa!" One of the children who were with her asked, "What is Africa?" to which Narda replied "It is a continent." The other friend asked her what a continent was and Narda said, with a little bit of exasperation "Come with me."

She then got out the globe and sat the older girls down for a very enjoyable lesson on the names of the continents and countries of the world. There is no reason to put off geographical studies until later grades. Children want to have an idea of where they live on a globe of Earth at very young ages.

Since this is the time when children love to do puzzles, and to know the names of everything in the environment, we follow the children's interests by offering puzzles of real value. Puzzle maps have been used in 3-6 classes for many years. Children easily "absorb" and memorize the relative sizes, the shapes, the location of continents and countries of the world in this motor-sensorial time of life. They delight in learning the names of every country and capital, the states, the rivers and mountains. These impressions are likely to stay with them forever.

We also give national songs, dances, instrumental music, costumes, pictures of state birds, flowers, flags, architecture, inventions, and adults and children carrying out the many aspects of life. We are very careful not to give the impression that any culture is superior in any way to any other. Each culture has its own strengths and weaknesses, its own gifts to the whole.

Flags of the world have a special attraction to children. Ideally every classroom has a set of the flags of the world.

A child might come in one morning with a story about India. She will gather all of the objects related to India in the classroom—a folder of pictures of Asia, the map of Asia with the puzzle piece of India, maybe a brass pitcher or statue from India, the flag of India, and so on. Often other children will join in the search, and maybe remind her of a song or poem from this country.

TEACHING HISTORY

In the "Age 3-6 Earth" section you will find materials for teaching the concepts of solar system, constellations, and physical geography that will eventually come together with experiences of cultural geography to give the child an excellent foundation for later studies of these subjects.

Biographies of famous and not-famous people are important pieces of the puzzle which will create the child's ultimate understanding of the history of the world. The adult begins this with stories about herself. One story I told over and over was about the experience of getting up one morning, going through the living room to fix breakfast and seeing our horse staring in the living room window at me. That's all, no plot, just a true experience, and the children loved it.

The mental construction of geography and history will come together in a different way for each child. It is our responsibility to arrange for many varied and interesting experiences that inspire the child to want to know more.

|

Today those things that occupy us in the field of education, are the interests of humanity at large and of civilization. Before such great forces we can recognize only one country—the entire world.

—Montessori

At six, there is a great transformation in the child, like a new birth. The child wants to explore society and the world, to learn what is right and wrong, to think about meaningful roles in society. She wants to know how everything came to be, the history of the universe, the world, humans and why they behave the way they do. He asks the BIG questions and wants answers. These children explore manners (and bad manners!); they are interested in religion and what it means to people in different cultures. It is the time to use the mind to explore all areas of knowledge, to begin to conduct research, and to develop creative ways of processing, exploring, and expressing this knowledge.

A Montessori elementary teacher has spent many months learning to give individual lessons in all academic areas, and to guide the child's research. Although groups form spontaneously, the main work is still done individually—concentration protected from interruptions by scheduled required groups—the hallmark of Montessori education at all ages. This heals and fulfills the child, and reveals the true human who naturally exhibits the desire to work, help others, and make a difference in the world.

COOPERATION, PEACE, AND WORK

What good is knowledge if not combined with consideration for others. Peace is not studied as an independent subject, but with the study of examples from the past, and practice in serving food and helping each other.

Peace is the natural outcome of a method of education where children experience work with their hands and long periods of individual concentration and contemplation. In this way they are able to process and recover from all the input of our modern world. They learn that peace is not just the absence of war, but the way we treat each other in our daily lives, the way we communicate, and the way we solve problems. Peace begins inside us, at home, at school.

The acts of courtesy which he has been taught with a view to his making contacts with others must now be brought to a new level. The question of aid to the weak, to the aged, to the sick, for example, now arises. If, up to the present, it was important not to bump someone in passing, it is now considered more important not to offend that person.

While the younger child seeks comforts, the older child is now eager to encounter challenges. But these challenges must have an aim.

The passage to the second level of education (age 6-12) is the passage from the sensorial, material level to the abstract. A turning toward the intellectual and moral sides of life occurs at the age of seven.

—Montessori

The history of a people cannot be separated from the possibilities of the environment in which it develops, and the leadership of its great men and women. In the beginning of each year the children are introduced to the study of humankind with stories, beautiful books, maps, posters, timelines and other research inspirations. Throughout the six years in the elementary class, the child moves from the general to the specific in the following way:

Age 6-8: the emphasis at this age in the 6-12 class is on prehistoric life, and plants and animals. She learns how plant and animals developed based on their environment and the changing climate of the Earth. They study the amazing variety of species which leads naturally into the study of classification—and the study of botany and zoology

Age 8-10: the emphasis is on early civilizations, from tribal cultures and ancient civilizations to the development of modern cities. They study the causes and results of migrations and how this is connected to the development of language and cultures, and the sciences.

Age 10-12: the emphasis is on the child's national and state history. The foundation has been laid in the first four years of the 6-12 class and this makes the study of one's own continent, country, state, county, city, one's own culture, make sense.

Of course all of these studies are going on at the same time and the child is free to follow her interests, no matter what the age. It is reinforced by the very important element of the Montessori class, that is that children teach each other, and they go to each other for help. The 6-year-old is exposed to the work of the 11-year-old, and the older child improves and increases her own knowledge because of the act of teaching someone else.

History is essentially a record of how humans fulfilled their physical, mental, and spiritual needs. These can be thought of as:

(1) Physical needs: food, clothing, shelter, transportation and defense

(2) Mental tendencies: work, exploration, creation, communication, play

(3) Spiritual needs: self respect or self love, love of others, creative love and the love of God

These subjects are also experienced subjectively in the classroom. For example, as the child learns about how different people obtain food, he learns to grow and prepare food. As he learns about clothing he may learn to knit or to make clothing or costumes. He studies the arts of other cultures while developing his own musical and other artistic talents. And while studying the ethics and religions of other cultures he is exploring his own relationship with friends, family and God. This creates, not only new abilities, but also an empathy with members of other cultures in the present and the past.

Those who do not remember the past are condemned to relive it.

—George Santayana, Philosopher, Harvard University

AMERICAN HISTORY & GEOGRAPHY

American History begins with the study of those who first arrived on this continent, not the immigration of Europeans. It is the story of the Native Americans and the people from all over the world who have settled here.

American History Timeline: An excellent way to make this point is to take a long role of adding machine paper and put the dates from, say 20,000 BC (or whenever humans arrived in North America according to the most recent archaeological findings) to the present.

Then make little cards with pictures and dates to show the relationship of events in time. Some suggestions are "crossing the Bering Straits," "Height of Aztec civilization" (and as many other Native American events as you and the children can find) "Columbus arrives", "TV was invented" and so forth. Laying the cards gives an impression or overview of American History. Use timelines for any subject.

BIOGRAPHY

The first "biographies" they study are their parents, their friends, and their teachers—and this begins early. As teenagers, our children will operate on information—about relationships, marriage, parenting, teaching, working, honesty, love, and so on—that they learned from living with us! As our children go on to learn about the great men and women of the past it is important that we remind them that these people all started out as children—and that the potential to be great and to contribute to the world is in all of us.

The study of history, biography, geography in the Montessori elementary class is different each year. There are basic lessons that the teacher gives at the beginning of the year to present an overview and an outline for research. But one never knows where the children will take it, where the individual interests will lead. This is thrilling for the teacher and the children alike, and the children never forget what they learn.

|